Flowering plants (angiosperms) are the largest, most diversified, and most successful major lineage of green plants, with ~330,000 known species. So far, the widely accepted classification of Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), which was first proposed in 1998 largely based on molecular phylogeny, has been updated to the fourth edition (APG IV). In the past decade, the accelerated development of high-throughput sequencing technology has provided a great impetus for phylogenetic studies of angiosperms, and a large number of phylogenetic studies adopting hundreds to thousands of genes across a wealth of clades have emerged and ushered plant phylogenetics and evolution into a new era— the era of phylogenomics. It is of great significance to summarize the research progress in phylogenomics of flowering plants with prospects in future studies.

Prof. LI Dezhu’s research team, from the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KIB/CAS) has been engaged in angiosperm phylogenetic and evolutionary genomics for decades. Based on their own expertise and extensive literature survey, the team reviews state of the reconstruction of the flowering plant tree of life, and discusses the major challenges faced by phylogenomic studies.

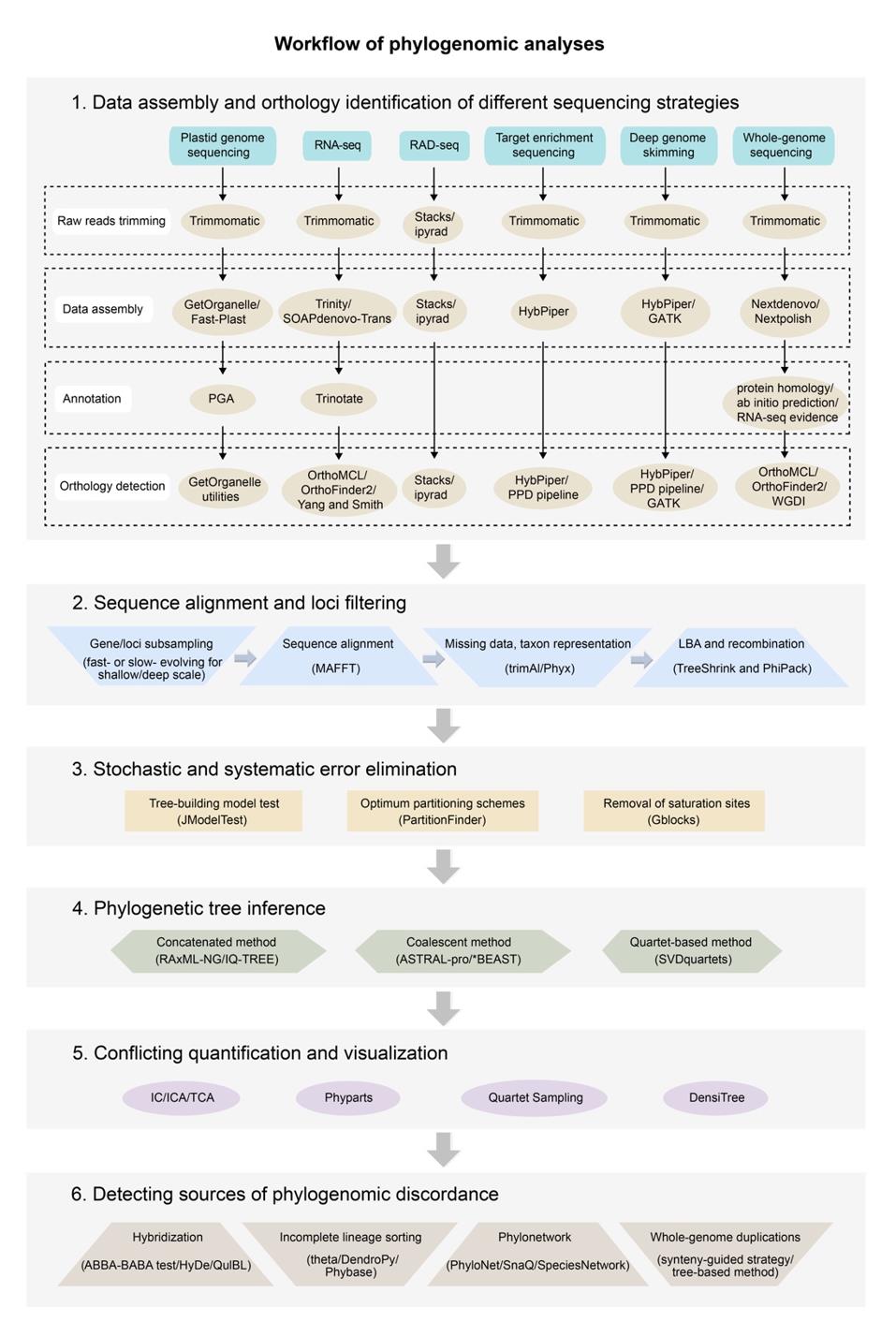

The review first outlines the current sequencing strategies, including genome skimming, transcriptome sequencing, restriction site-associated DNA sequencing, target enrichment sequencing, deep genome skimming, and whole-genome sequencing, and discusses the advantages, shortcomings and potential applications of each. A workflow for plant phylogenomic analyses was provided for practical applications (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Workflow of phylogenomic analyses (Image by KIB)

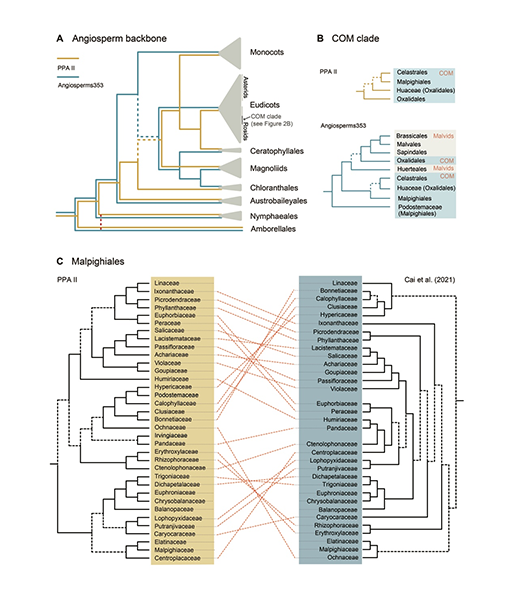

The review also summarizes recent developments in the use of genomic data for phylogenetic reconstructions of flowering plants at various taxonomic levels (Figure 2), and highlights their potential impact on taxonomic treatments. The review further discusses the major challenges, such as the adverse impact on orthology inference and phylogenetic reconstruction raised from systematic errors, wholie-genome duplicatin (WGD), hybridization/introgression, and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and makes practical recommendations for phylogenomic studies of complex evolutionary lineages.

Figure 2. Notable recalcitrant or reticulate relationships at the familial level and above based on recent phylogenomic studies (Image by KIB)

Finally, this review comments on angiosperm phylogenomics from four aspects: (1) As more and more unresolved relationships emerged across major flowering plant lineages, dichotomous branching phylogenetic trees, in some cases, may not be the best evolutionary model for the angiosperm tree of life, and it is hoped that development of network-based approaches would improve our ability to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships and infer evolutionary processes; (2) Whole-genome sequencing is an inevitable trend in years to come, and the increasing accessibility of genomic data would continue to deepen our understanding of angiosperm evolutionary history; (3) The majority of phylogenomic studies focus on restricted geographic and taxonomic scopes, and a more balanced development through global collaboration is urgently needed; (4) Integrated analysis of omics data coupled with morphological, ecological, and ultimately multi-disciplinary evidence is critical for a more complete understanding of plant evolutionary history.

The review entitled “Phylogenomics and the flowering plant tree of life” has been published in the Journal of Integrative Plant Biology.

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS, and the Large-scale Scientific Facilities of CAS.

(Editor:YANG Mei)