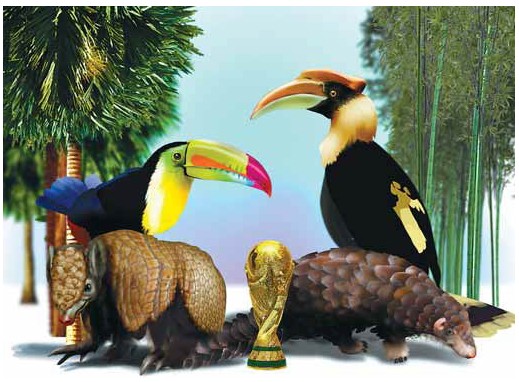

SIMILAR BUT NOT THE SAME: Although they look alike, the pangolin is of the order pholidota, while the armadillo is classified as part of the order cingulat. A newspaper erroneously labeled the toucan as the “god bird” of the Jingpo people in Yunnan. In truth, that bird is the hornbill.

In the run-up to the FIFA World Cup 2014, Chinese soccer fans have been attempting to wrap their tongues around some of the exotic names from the national squads, with Sokratis Papastathopoulos and Lazaros Christodoulopoulos of Greece, and Reza Ghoochannejhad of Iran among those that have proved the most perplexing.

However, the most popular name by far isn't that of a human being, but a shy, retiring creature called the Brazilian three-banded armadillo, or the tatu-bola, which has been chosen as the mascot for the world's biggest soccer tournament, which begins in Brazil on Thursday. The name, which is Portuguese in origin, comes from the animal's ability to curl up into a ball, or bola, at the first hint of trouble. In fact, it's one of just two species of armadillo that can achieve this feat.

"It's the first time I've seen the name of this animal, and I have no idea how to pronounce it," wrote "Sweet Sugar" on her micro blog on Sunday. Her post prompted scores of comments from netizens, most of whom were equally mystified.

Having learned the correct pronunciation, many people turned their attention to gathering facts about the tatu-bola. Guokr, one of China's top websites for science enthusiasts, has published several short introductory articles via its micro blog in response to questions from the public about the living habits, diet and place of origin of the animal, known in Chinese as qiuyu.

Online sports chatrooms and Sina Weibo - the Chinese equivalent of Twitter - have been bombarded by soccer fans discussing the qiuyu. Meanwhile, on soccer.hupu, a popular bulletin board site, a fierce discussion has raged over whether the tatu-bola has blood ties with the Chinese pangolin.

Physically, the two animals have marked similarities: Both have long snouts, strong claws and the same sort of protective armored shell. To the Chinese, the pangolin is a familiar creature, partly because it has been used in countless cartoons, where its amazing skill at digging holes is fully illustrated, and also because its scaly epidermal armor is used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat inflammation of the breast tissue, among other conditions.

Unrelated 'relations'

However, to many people's disappointment, zoologists have refuted claims that the animals are related. "They are totally different and belong to entirely different orders. The Pangolin is classed under the order Pholidota, while the armadillo is a member of the order Cingulata," said Wang Yingxiang from the Kunming Institute of Zoology, under the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

"The armadillo is indigenous to Brazil and doesn't exist in the wild outside South America," Wang said. "The only real characteristic shared by the armadillo and the Chinese pangolin is their favorite food - white ants."

But how can it be that two animals that look almost identical and share similar habits are not even distantly related? The answer lies in the way in which scientists classify living things.

The modern system of biological classification was introduced by Carolus "Carl" Linnaeus (1707-78), a Swedish physician, botanist and naturalist. The system - which is built on seven categories: kingdom; phylum; class; order; family; genus; and species - is like a mathematical tree graph, where the kingdom is the main stem and the species are the branches and twigs.

According to Rao Dingqi, an expert on amphibians at Kunming Institute of Zoology, the time scale required for animals to develop into two orders usually takes tens of millions of years, and then additional millions of years for creatures within the same order to develop into distinct families. "This may help people to understand the extent to which two animals can differ from each other," he said.

Cingulata consists primarily of armadillo-like animals, according to Wang, and the name refers to the girdle-like shell of present-day armadillos. The armadillo is the only surviving member of Cingulata, and the five other species that were once in this order are now extinct and are only known from fossilized remains.

Wang said the pangolin's scaly epidermal armor gives it the appearance of a pine cone and necessity has forced it to develop strong, clawed limbs to help it tear apart termite nests.

"Pangolins have no teeth. So for several years they were placed in the order Edentata," Wang said. "However, they also lack several skeletal structures unique to the edentates, so they were placed in their own order. That's how scientists work to classify animals. It's not based on appearance, but something 'deep' under the skin," he said.

The 'god bird'

Cute though the tatu-bola is, some Brazilians were surprised by their country's choice of "Fuleco", as the mascot has been named. Lidia Ferranti, a lawyer in Sao Paulo said she isn't fond of the mascot, but understood why it had been chosen. "I think it's a good idea to choose it as our mascot because it's a Brazilian animal and we have a lot of them in our country," she said.

Conversely, Matheus Tales, a student from Moura Lacerda Central University, was adamant that the choice was wrong. "It is not a famous animal in Brazil, and I don't think it will help foreigners to remember Brazil in the same way they remember the panda from the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games," he said, adding that he would like to see a panda in Brazil at some time.

Ferranti agreed with that sentiment. "I think the panda is one of the cutest animals in the world, and I really hope to see one with my own eyes some day," she said. "I hope the Chinese government will loan one to Brazil, as it has other countries. I'm sure that all Brazilians would like the idea and would visit the zoo just to see it."

Tales has his own suggestion. "I think the toucan would have been a much better choice," he said. "It's lovely and is also known by a greater number of people internationally."

The toucan is instantly recognizable globally after the success of Rio 2, an animal-themed animation that took more than $16 million at the box office in the week after it opened in China. "Rafael", a suave and charming toucan with a huge black and yellow bill, made a strong impression on Chinese audiences.

As Rafael's popularity grew, a newspaper in southwest China reported that the toucan may have originated in the southwestern province of Yunnan. "It was adopted as a 'god bird', connected to the god once worshipped by the Jingpo ethnic group in the south of the province," the newspaper said.

Sadly, the supposition is incorrect, according to avian experts. "The toucan's home is the tropical forests of South America. Its oversized, colorful bill has made it one of the world's most popular birds," said Yang Xiaojun of the China Ornithological Society.

Toucans usually lay two to four eggs a year in their nests, hidden away in holes in tree stumps. Both parents care for the chicks. Young toucans do not have a large bill at birth - it grows as they develop and does not reach its full size until several months after hatching. The birds are very popular as pets, and many are captured to supply the trade.

"We do have a beautiful bird with a large, colorful bill in China. And it is indeed the 'god bird' for the Jingpo people in Yunnan," said Han Lianxian, an avian expert at Southwest Forestry University. "But the name of the bird is the hornbill, not toucan."

Hornbills originated in tropical and subtropical Africa, Asia and Melanesia, and are characterized by a long, downward-curving bill, which is frequently brightly colored and sometimes has a casque, a small helmet-shaped structure, on the upper mandible.

The birds are omnivorous, feeding on fruit and small animals, according to Han, who said hornbills are monogamous and nest in natural cavities in trees and sometimes on cliffs. A number of hornbill species - mainly the insular species with limited flight range - are on the verge of becoming extinct.

According to Han, the long bills of both toucans and hornbills have a number of functions. As a weapon, the bill is more for show than substance, but it's a very useful feeding tool. The birds use their bills to reach fruit on branches too small to support their weight, and also to skin their pickings.

"One species called the wreathed hornbill is a famous commercial mascot known for its casque-made decorations," Han said, adding that the bird has been listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, and is under State protection.

Tree of life

There are many similarities between the flora of Brazil and China, but, once again, appearances can be deceptive.

"In fact, botanical species are also totally different in the two countries," said Shui Yumin, a botanist from Kunming Institute of Botany at the Chinese Academy of Science, who undertook a scientific expedition to French Guiana earlier this year.

He said South American plants are usually more brightly colored and larger than their Chinese "counterparts".

"Unlike plants in South America, which mainly rely on bees for pollination, plants in Asia usually depend on birds or even bigger animals, such as monkeys, to disperse their seeds," Shui said. As with animals, botanical taxonomy also classifies flora based on several factors, including physiological, chemical and also metabolic characteristics.

"Appearance just counts for one of millions of reasons that suggest 'blood ties' between two species," Shui said. In terms of botany, China has a unique character. "There's a wider range of botanical diversity here, including 'ancestor' species and highly evolved sub-species," he said, adding that diversity in South America is illustrated by the wide variety of genera and species.

Shui used the image of a tree to illustrate his point: "The botanical system in Asia is like a pine tree with well-proportioned stems, branches and leaves, while the system in South America is like a coconut tree in that most of its characteristics are at the top," he said.

Proving a close relationship between plants in Brazil and China appears extremely difficult, but Shui said a few well-known Chinese staples definitely originated in the South American country.

Corn, chilies and even potatoes were all imported from Brazil, and their pleasant tastes and ease of cultivation ensured that the three plants quickly spread across China to become staple foodstuffs.

"Continental drift resulted in connections between living things on Earth. However, hundreds of millions years of development resulted in a huge number of distinctive features. In some cases, people have been confused by the apparent similarities and have raised questions or doubts. And that's a good thing, because science is the process of knowing," Shui said.

Source:http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/2014-06/10/content_17574264.htm