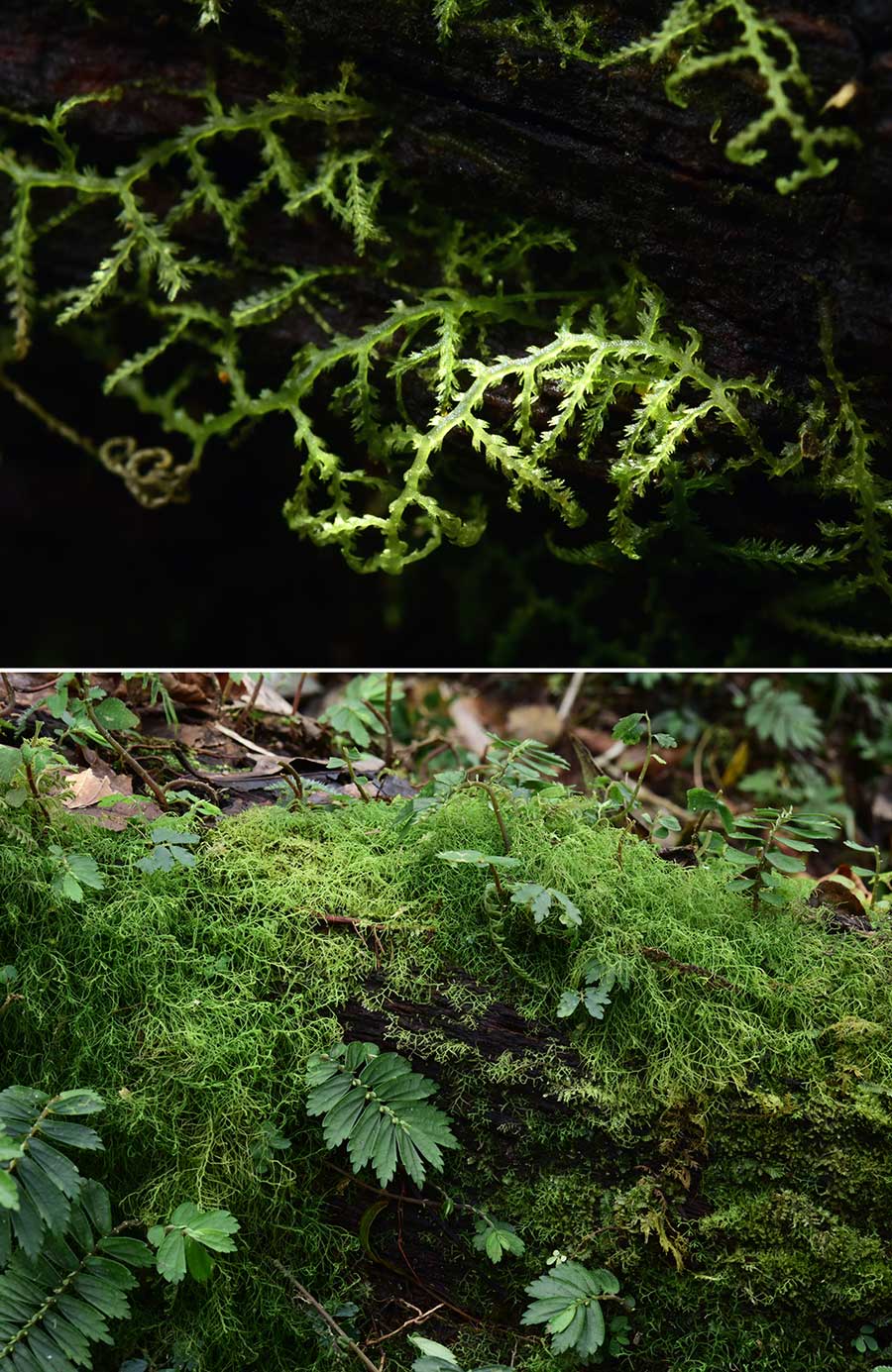

Mosses are beautiful and dynamic in the eyes of botanist Ma Wenzhang, who has collected about 2,000 species found in China. [Photo by Ma Wenzhang/China Daily]

The old saying "a rolling stone gathers no moss" has evolved over the years, coming to mean that one must keep moving in order to stay fresh and keen, particularly when it comes to a career. But, what about those who are always moving around, doing so to literally only gather moss?

People like Ma Wenzhang from Chongqing, for example.

You see, in this age of information, having so much knowledge at one's fingertips is only made possible because of those that seek it out in the first place. As such, when it comes to things like botany, collecting specimens still relies on manual work-people still need to go deep into the forest to pick and identify the plants.

Unlike common specimen administrators who spend most of their time in the herbarium, 39-year-old Ma enjoys fieldwork. His colleagues think he is a "weirdo"-he hikes, climbs, eats wild mushrooms and sleeps with animals, all just to collect moss samples.

He often sleeps in farmers' homes, forest rangers' sheds or just camps outdoors.

Ma is responsible for collecting bryophyte specimens for the Herbarium of Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the second largest herbarium in China.

"The value of specimens is the preservation of information. We can't go back to the past, but through specimens, we can compare the difference in environment between decades or even centuries, learn about pollution levels in the past, and even extract DNA information," Ma says.

Each year, he spends around three months in the field, with each trip averaging seven to 15 days. Over the past decade, he has carried out nearly 70 expeditions and collected more than 11,000 bryophyte specimens.

"The small moss can easily be missed by people, but I can recognize it at a glance and identify its species, which is pretty cool," Ma says.

Mosses are beautiful and dynamic in the eyes of botanist Ma Wenzhang, who has collected about 2,000 species found in China. [Photo by Ma Wenzhang/China Daily]

Ma usually shares his excursions with several scientists specializing in other disciplines, such as fungi or insects. Upon entering the forest they separate, each hunting their own targets, then meeting back at the starting point at an appointed time.

Ma is always the last one to return because he is so focused on taking photos of the moss he finds along the way, before stopping to collect samples on his way back. He is usually able to photograph the whole research team on the mountain, because they are all ahead of him.

Getting lost is a common occurrence for Ma. "There are two rules to follow if you find yourself lost. Number one is not to panic and the other is to move toward the lower terrain or along the water," Ma says. "If I realize I'm lost and I don't recognize anything in any direction, I'll turn back."

A video production team once followed him on a 10-hour hike to collect moss in Yangbi Yi autonomous county, Yunnan province. It was a rainy day and they walked on a previously untraversed route for three hours before realizing they were lost.

"If we don't go far enough to reach a place with the right environment, we can't find the best moss," Ma, who felt a bit guilty, explained to the team.

Ma used to be afraid of leeches in the woods. He would dream of leeches for days after being bitten and would always suspect there were leeches in his bed.

"Now, however, when I see leeches I feel happy, because it means there is not too much pollution," Ma says, whose first reaction these days when encountering leeches or snakes is to take photos of them.

Ma has visited all the nature reserves in Southwest China. The one he finds most impressive, and which he has visited three times, is Wutai Mountain on the border between China and Vietnam.

"Even on the same route, I collect different moss species each time, because mosses are dynamic-it's random for some species to show up in certain places, and when you visit the same place after several years, you may see a totally different species."

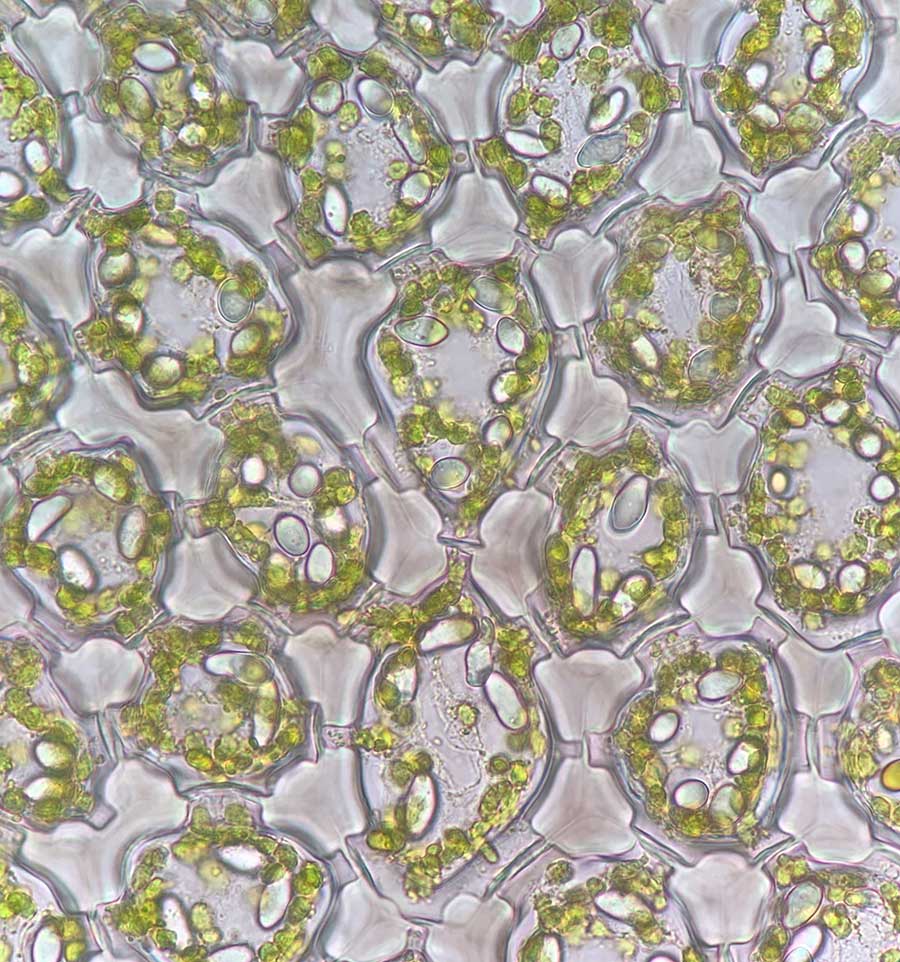

A group of leaf cells of a moss under a microscope. [Photo by Ma Wenzhang/China Daily]

A passion grows

Ma liked to observe plants and insects when he was a kid. He studied conservation of water and soil and desertification control at Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University in Yangling, Shaanxi province.

He moved to Yunnan in 2004 to study his master's and doctoral degrees in ecology at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and started to learn more about moss, which became his main focus after graduation.

Even though moss species are small, they are one of the oldest plants on Earth, showing up 400 million years ago, 150 million years earlier than dinosaurs. According to Ma, there are more than 20,000 species of bryophytes, and China has around 3,400 to 3,600 species. He has collected samples of roughly 2,000 species so far.

Ma thinks bryophytes play a vital role in regulating ecosystems because they provide an important buffer system for other plants, as well as being pioneers by growing in environments that higher plants can't survive.

"Bryophytes also support biodiversity on Earth," Ma says. "They can be found in cities and villages and also can be made into a decoration in our homes."

A new moss genus from Shangri-La of Diqing Tibet autonomous prefecture, Yunnan province, which was discovered by Ma, was named after him in 2018-Mawenzhangia thamnobryoides-a great honor for a specimen worker.

Ma thinks to collect moss fits the Pareto principle-to find the 20 percent of rare species takes four times as long as finding a common species. "When you see a really good sample, you will be amazed by its shining light," he says.

After collecting the moss, Ma puts them into bags made of strong smooth wrapping paper and he needs to dry them on the same day. "It's an easier job compared to other botanists, as they have to prepare their specimens at our field headquarters, whereas I can wait to do that work when I return to the lab," Ma says.

Ma says the lab work actually takes seven times longer than that of the field trip. The identification of the specimen is important work for Ma. He sometimes sends the specimen to specialists all over the world to ask for their insight.

"It's one way to learn about the process of identifying," he says.

To observe the mosses under a microscope is also where Ma finds the true beauty of his specimens. "It's interesting to see the regular cellular structure of the mosses," Ma says.

Zhang Li, director of bryophytes professional committee of the Botanical Society of China, has been studying moss for three decades. Even though the subject is still a niche field, he has witnessed the slow, but sure, domestic expansion of moss lovers.

"There were fewer than 20 specialists studying bryophytes in China 30 years ago. Now, including students, we have around 100 people focusing on this niche subject," Zhang says.

He has known Ma for a decade and has accompanied Ma on field trips a couple of times.

"Ma can bear hardship. He spends a lot of time in the field, especially some places deep in the mountains, to collect samples," Zhang says. "He has the sharp eyes to find moss in the forest at a glance." (China Daily)

Mosses are beautiful and dynamic in the eyes of botanist Ma Wenzhang, who has collected about 2,000 species found in China. [Photo by Ma Wenzhang/China Daily]

He takes photos of an aquatic moss in Malipo, Yunnan. [Photo by Yang Yingbo/China Daily]

(Editor:YANG Mei)