Seed dispersal is an essential process for plant reproduction and the maintenance of ecosystem functions. A large fraction of plants is dispersed by vertebrates, mostly birds and mammals which feed on fruits and release the seeds once they passed through their digestive tracts – a mechanism called endozoochory.

Seed dispersal by invertebrates, however, have received much less attention, apart from apart from ant-mediated dispersal (myrmecochory). Reports of dispersal by invertebrates, such as wasps, wetas, beetles or slug, are often considered anecdotal natural history oddities. However, evidence suggests that some invertebrate group could be important dispersers, and their role remain largely unexplored.

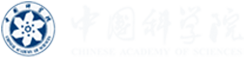

With over 150,000 species, Diptera (flies) are one of the largest and most widespread insect group. Despite this, no cases of seed dispersal by flies are known. Among them, flies of the genus Bengalia are especially unique: they rob food and offspring transported by ants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bengalia flies robbing food or offspring transported by ants: larvae and pupae of ants (A&B), termite (C), breadcrumbs (D), and insects from Lepidoptera, Orthoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera (E-I). (Image by KIB)

These flies form a unique interaction known as obligate ‘kleptoparasitism’: you could offer them their favorite food, but they would not touch it and starve to death unless it is carried by an ant and they can steal it. The geographic distribution of Bengalia flies encompass a large part of Asia and tropical Africa, overlapping with plant dispersed by ants (myrmecochorous plants). Because seed dispersal by ants involves ants carrying plant seeds, Bengalia could steal them and thus interact with the dispersal process, but this remained unknown. A research team lead by Prof. CHEN Gao at the Kunming Institute of Botany , Chinese Academy of Sciences (KIB/CAS) tested this hypothesis.

Through long-term field observations and multi-year bioassays, Prof. CHEN’s research team provided the first empirical evidence confirming flies as effective seed dispersers. The first insight occurred when Prof. Chen’s team offered seeds to ants in a site where Bengalia were present. Immediately after the ants collected and started to transport the seeds, the flies were attracted to the site and stole the seeds, flying with them.

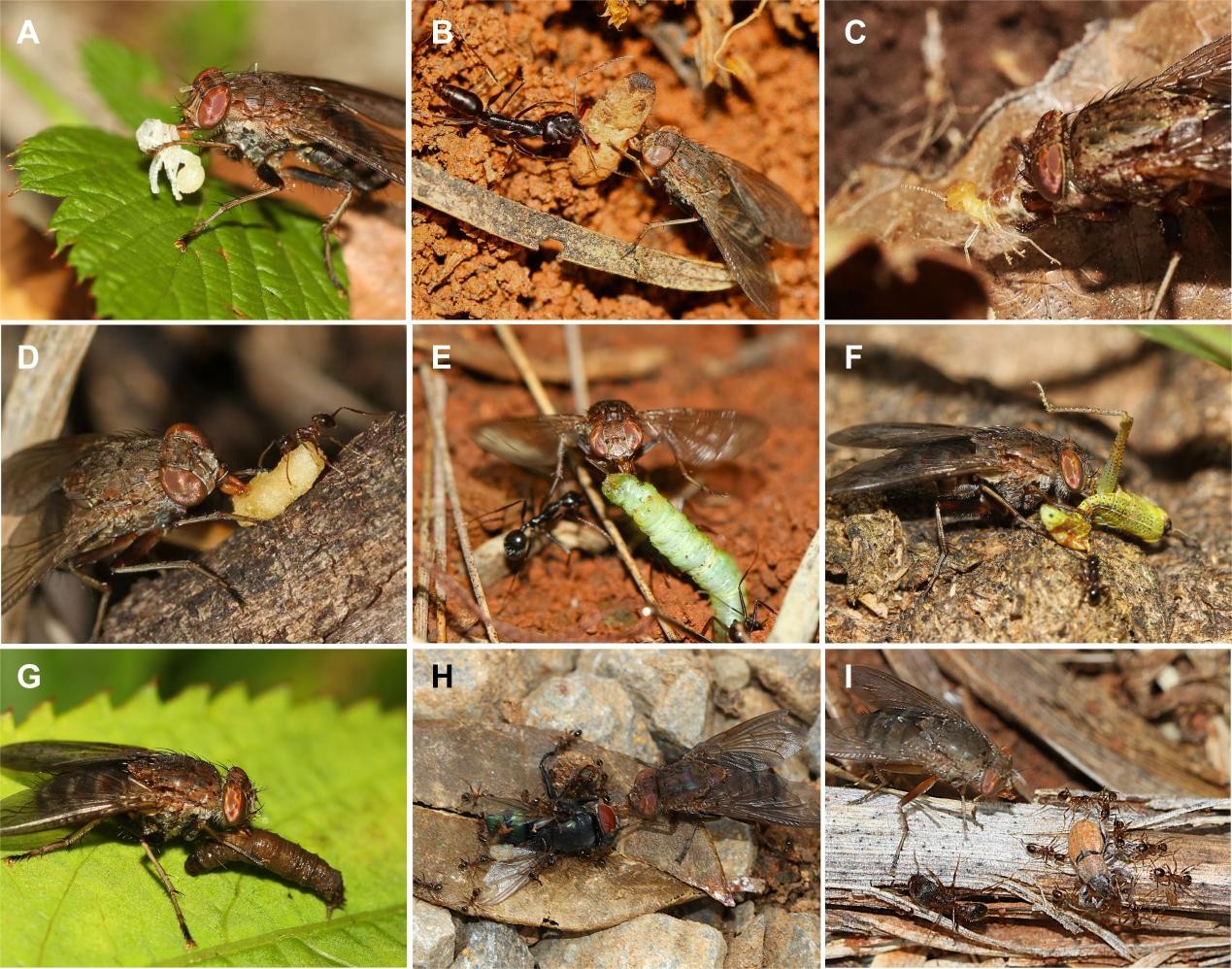

The study discovered that Bengalia varicolor actively rob seeds transported by ants, and dispersed them further away and to more areas than they would without the fly – establishing a novel seed dispersal mutualism (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bengalia fly robbing a seed of Stemona mairei being transported by ant. (Image by KIB)

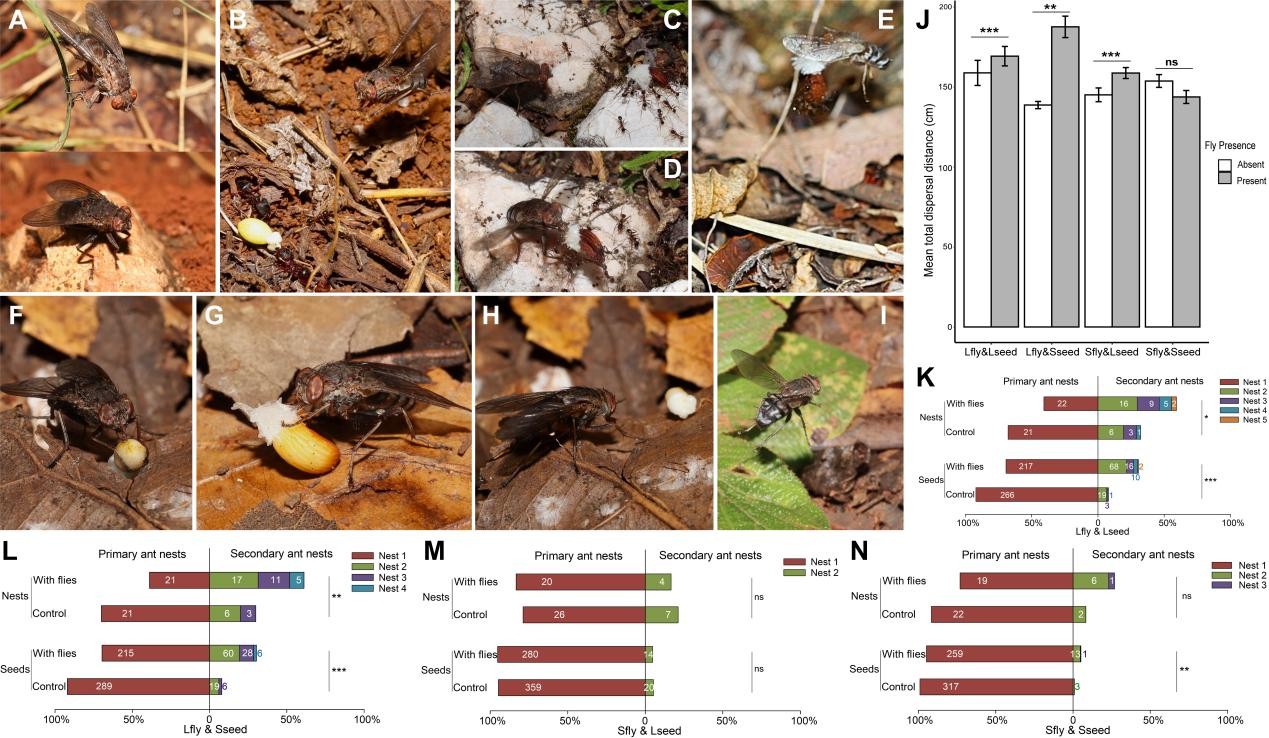

The mechanism involves several key steps: Bengalia flies are attracted to seed-carrying ants, observe them from elevated positions, dive to intercept, grasping the seed firmly with their forelegs, and repeatedly taking off to dislodge the ants that impede their behavior. The flies then consume the seed’s nutrient-rich appendage (elaiosome) before discarding the seed (Figure 3).

Discarded seeds are often rediscovered and dispersed again by other ants, revealing the intricate ecological interplay between animals and plants. The relationship is beneficial for both (mutualism): the plant gets an enhanced seed dispersal than in the absence of the flies, while the fly feeds on the nutritious seed appendages (elaiosome).

To quantify the impact of Bengalia flies on the myrmecochory process, the team designed systematic experiments comparing seed dispersal patterns with and without Bengalia participation and investigated size-matching effects between flies and seeds (large/small flies vs. large/small seeds), with a total of 172 experimental treatments and 2580 seeds.

These experiments yielded several key findings. First, Bengalia flies substantially increase the seed dispersal distance. Second, they allowed the seeds to reach any more potentially suitable germination sites, with the seeds being typically recollected and re-dispersed by ants.

This represented a completely novel type of seed dispersal that works in relay: ants disperse the seeds; Bengalia flies rob them, and disperse them further; the the ants then re-collect and dispersed the discarded seeds. The same seeds could then be stolen again by Bengalia, and the team’s discovered that such mechanism could involve up to 7 cycles alternating dispersal between ants and flies.

This relay dispersal between flies and ants—a new form of diplochory (seed dispersal involving several dispersal agents)—significantly extends seed dispersal distance, range, and suitable microhabitats (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sequence of Bengalia flies robbing a seed from a transporting ant (A-I); and comparisons of seed dispersal distance (J), and the number of ant nests reached and seeds entering each nest (K-N), with and without Bengalia presence. (Imag by KIB)

This study elucidates a specialized seed dispersal mechanism based on the kleptoparasitic behavior of Bengalia flies. It relies on initial ant transport and frequently triggers subsequent dispersal by other ant colonies.

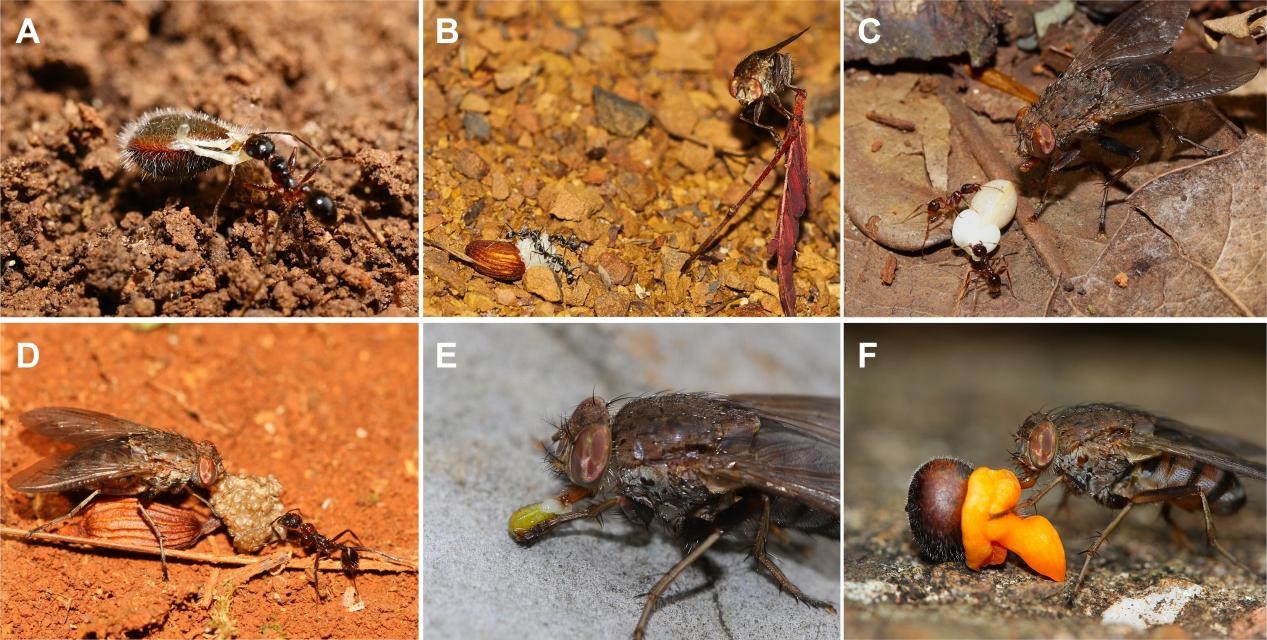

The research also revealed that Bengalia exhibits generalized seed dispersal behavior (involving plants from Stemonaceae, Celastraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Melanthiaceae, Papaveraceae, Polygalaceae, etc.), with its geographic distribution showing broad overlap with myrmecochorous plants (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Bengalia flies dispersing seeds of different plant groups: Polygalaceae (A & F), Stemonaceae (B & D), Celastraceae (C), and Papaveraceae (E). (Image by KIB)Thus, given the large overlap between ant-dispersed plants and Bengalia flies, it is likely that seed dispersal by flies is a widespread seed dispersal syndrome across Asia and Tropical Africa. More work across Bengalia’s range is necessary to confirm this – which would be a complete paradigm shift in our understanding of seed dispersal. (Imag by KIB)

This work adds a new dimension—seed dispersal—to the known interactions between flies and plants, distinct from traditional relationships like flower visitation, pollination, herbivory, or parasitism. The recognition mechanism, involving Bengalia flies eavesdropping on ant trail and alarm pheromones to mediate seed dispersal, and the associated energy flow within this interaction, are subjects of ongoing research.

The findings, entitled "Seed dispersal by kleptoparasitic flies" have been published in the prestigious journal Current Biology (Cell Press).

Dr. YU Yulong (Postdoctoral Fellow, KIB, CAS) and Professor Guillaume Chomicki (Durham University, UK) are co-first authors, with Researcher CHEN Gao serving as the corresponding author.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32371564), and other funding sources.

Contact:

YANG Mei

General Office

Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS

email: yangmei@mail.kib.ac.cn

(Editor: YANG Mei)